Over the course of her career, science fiction and fantasy writer Elizabeth Moon has published 21 novels (so far), and been awarded both the Nebula award and Heinlein award.

Byrt: You once mentioned that Anne McCaffrey solved a story problem for you with a lift of her eyebrows. I’ve always wondered – do you happen to remember what that problem was?

EM: Unfortunately, I don’t. (I’m over 65 now and wrote that book approximately eight years ago…can I use that excuse?)

EM: Unfortunately, I don’t. (I’m over 65 now and wrote that book approximately eight years ago…can I use that excuse?)

Byrt: And what was it like, working with Anne McCaffrey on the Planet Pirates series?

EM: Absolutely wonderful. She’s the most gracious senior writer a junior writer could hope for. I learned so much — both her generosity in letting me play in her sandbox, and her guidance, were enormously helpful.

Byrt: As someone who has written SF/F for over two decades now, are things in any way different today than they were when you started? For better or for worse?

EM: Different, yes, especially in how the work is done and communicated. My first published work (nonfiction) was written on a typewriter and delivered as paper, with enclosed SASE. I switched from typewriter to computer partway through the Paks books, but still had to submit everything on paper–with attendant high postage costs. Communication with agent, editor, and others was by phone or post. (My first overseas phone conversations were with Anne McCaffrey.) Then we finally got internet connections–and I could email back and forth with people. Then I could send files…and finally whole manuscripts. All that’s on the “better” side of things.

I’m not as thrilled about all-electronic workflow (editing using Track Changes, for instance.) When anything more than one or two-word changes needs to be made, I find it difficult to re-create the “flow” of the text with those colored interruptions bumping into my sense of the sound of the language — so it’s hard to make the best choices. I know it’s faster for the publisher, without the risk of loss or delay in the mail, but it’s harder for me. Some people, however, find it much easier. My editor doesn’t make me do everything in Track Changes, which I’m grateful for.

I’m not as thrilled about all-electronic workflow (editing using Track Changes, for instance.) When anything more than one or two-word changes needs to be made, I find it difficult to re-create the “flow” of the text with those colored interruptions bumping into my sense of the sound of the language — so it’s hard to make the best choices. I know it’s faster for the publisher, without the risk of loss or delay in the mail, but it’s harder for me. Some people, however, find it much easier. My editor doesn’t make me do everything in Track Changes, which I’m grateful for.

More generally, the well-known economic problems in publishing have hit most of us, and the new opportunities in internet communications and publishing didn’t take up the slack as fast as the problems developed. Even experienced, previously successful writers have had difficulty finding any stability in which to work. That’s beginning to shift now, with some people beginning to make real money from publishing fiction themselves online. Cooperative outlets such as Book View Cafe and Backlist Ebooks, organized by professional writers, make it much easier for writers to sell their out-of-print backlist works and publish works that aren’t likely to find a market in traditional publishing (like the Breaking Waves anthology, novellas related to books, etc).

Byrt: Would you consider your Paksenarrion series a lovechild of Tolkien? :) And did you ever worry about straying too far into his shadow?

EM: In the sense of allowing myself to sink into a “big world” project, probably, but there’s a huge difference in background. I’m not a philologist or linguist; my first degree, in history, emphasized legal and economic strands of history, which are pretty much absent in LOTR, but very obvious in the Paks books. And then there’s the gender thing…

EM: In the sense of allowing myself to sink into a “big world” project, probably, but there’s a huge difference in background. I’m not a philologist or linguist; my first degree, in history, emphasized legal and economic strands of history, which are pretty much absent in LOTR, but very obvious in the Paks books. And then there’s the gender thing…

I was swept away by Tolkein’s worldbuilding and use of language — I still re-read not just the most obvious, but some of his shorter fiction (Leaf by Niggle, for instance.) So his work is certainly an influence, but not the only one. I didn’t worry about being in his shadow…for decades, I wrote for myself alone, so that wasn’t even a passing thought. The Paks books started that way — a private indulgence.

Byrt: I just want to say thank you for how you dealt with the issue of rape in Once a Hero – thank you for showing the damage without victimizing the woman, and for showing that there is no shame in needing help. Was this an issue you wanted to write about, or did it just happen organically within the story? Were you nervous about touching such a hot-button topic?

EM: I didn’t plan to write it — it was definitely organic. Esmay, in her first appearance in Winning Colors, intrigued me and seemed to need an explanation. She surprised everyone, including herself…so I started Once a Hero to find out more about her. Why had she hidden her talent, and was it conscious or unconscious?

EM: I didn’t plan to write it — it was definitely organic. Esmay, in her first appearance in Winning Colors, intrigued me and seemed to need an explanation. She surprised everyone, including herself…so I started Once a Hero to find out more about her. Why had she hidden her talent, and was it conscious or unconscious?

Nervous, yes, once I realized where it was taking me. At the time, there was a lot of controversy about whether memories of childhood abuse were all true, all false, or somewhere in between…and what the consequences were for both the child victims and the adults who did or did not help the child recover. Some people still argue that many accusations of rape are false, that children are seductive and initiate sex willingly, that therapists do more harm than good. Also nervous because including any hot-button topic in a book brings assumptions about the writer’s source of knowledge…did he/she experience what’s being written about?

Byrt: I love your Vatta’s War series and was fascinated by Ky Vatta’s inner struggle with her killer instincts, and how it made her question what kind of person she was. Was her story inspired by your time in the Marine Corps?

EM: Most of my books draw on that experience, and undoubtedly I’d have used military settings (for either fantasy or science fiction) a lot less without it. So in that sense, yes — as part of a continuing interest in the interaction between character and overt, violent conflict. But the specific inspiration for that group of books went beyond my personal military experience. In the Serrano/Suiza books I’d written about families with a tradition (military in the case of those two, and civilian public service in the case of other main characters.) In military families, children learn the rules of their parents’ service by osmosis…which can make the choice of career inevitable whether or not the child is suited to it, and whether or not that family’s version of the cultural ethos suits the new war. In political families, much the same.

EM: Most of my books draw on that experience, and undoubtedly I’d have used military settings (for either fantasy or science fiction) a lot less without it. So in that sense, yes — as part of a continuing interest in the interaction between character and overt, violent conflict. But the specific inspiration for that group of books went beyond my personal military experience. In the Serrano/Suiza books I’d written about families with a tradition (military in the case of those two, and civilian public service in the case of other main characters.) In military families, children learn the rules of their parents’ service by osmosis…which can make the choice of career inevitable whether or not the child is suited to it, and whether or not that family’s version of the cultural ethos suits the new war. In political families, much the same.

What about characters who are not bolstered by such traditions? How do they discover their talent for the military? What pressures shift them that way? How is their experience different from those whose family expectations reinforce a military career? How do the family reactions to having a family member join the military affect that person’s commitment to service and performance? Are the mistakes they make any different from the mistakes made by those from a traditional military family? Are their applicable talents more or less likely to be recognized and used? I drew heavily on Dave Grossman’s book On Killing, which examined the effect of killing on military personnel through interviews with veterans of several wars for Ky’s struggle with her own nature and her gradual understanding of Aunt Grace. For the family-related issues, I drew on memoirs by veterans from both military and nonmilitary families.

What about characters who are not bolstered by such traditions? How do they discover their talent for the military? What pressures shift them that way? How is their experience different from those whose family expectations reinforce a military career? How do the family reactions to having a family member join the military affect that person’s commitment to service and performance? Are the mistakes they make any different from the mistakes made by those from a traditional military family? Are their applicable talents more or less likely to be recognized and used? I drew heavily on Dave Grossman’s book On Killing, which examined the effect of killing on military personnel through interviews with veterans of several wars for Ky’s struggle with her own nature and her gradual understanding of Aunt Grace. For the family-related issues, I drew on memoirs by veterans from both military and nonmilitary families.

Byrt: And again, thank you for writing in Vatta’s War about a warrior who is not weak for needing post-trauma therapy, and for her gender never once being considered a factor. Again, was this naturally part of the story, or something you felt needed to be written about? And is seeking treatment still seen as shameful to most soldiers?

EM: It’s difficult to separate “naturally part of the story” from issues a writer cares a lot about. Though I usually don’t intend to write “issue” stories (because they turn into sermons and diatribes, not stories, more often than not), as a Vietnam-era vet, and a close observer of the military since, I was aware of the reality of PTSD in veterans and the inadequacy of treatment options. During ‘Nam, the public animosity toward both active-duty soldiers and vets ensured that treatment availability was minimal and seeking treatment — admitting a problem — brought scorn, not help, not only from commanders and fellow soldiers, but from the public.

EM: It’s difficult to separate “naturally part of the story” from issues a writer cares a lot about. Though I usually don’t intend to write “issue” stories (because they turn into sermons and diatribes, not stories, more often than not), as a Vietnam-era vet, and a close observer of the military since, I was aware of the reality of PTSD in veterans and the inadequacy of treatment options. During ‘Nam, the public animosity toward both active-duty soldiers and vets ensured that treatment availability was minimal and seeking treatment — admitting a problem — brought scorn, not help, not only from commanders and fellow soldiers, but from the public.

Yet research done then slowly worked its way into both public and military perception; by the first Gulf War, many soldiers and their families knew such a thing existed, even outside a military context. By the time I wrote this book, there’d been considerable discussion in the military on the need for better mental-health interventions in PTSD. Today, with the strains that the second Gulf War has put on active-duty personnel, both the need and the awareness of the need is greater. Despite past experience and research, the need for expanded mental health services didn’t make it into the planning — let alone the funding.

The military is presently trying hard to eradicate the “seeking treatment is weakness” meme — but it’s still there, and not only in the military. The military ethos emphasizes physical and mental toughness, with the “mental” side usually relying on “willpower” and “character”– without training equivalent to physical training. People can’t “think their way” to physical fitness (as my waistline indicates!) and they can’t “will their way” to emotional resilience. They need to be taught how to deal with emotional traumas, have practice in those techniques. There are new programs aimed at pre-trauma instruction and post-trauma treatment, with specific directions to commanders not to ignore soldiers’ mental/emotional state, but it’s a slow transition. A lot of inertia.

The military is presently trying hard to eradicate the “seeking treatment is weakness” meme — but it’s still there, and not only in the military. The military ethos emphasizes physical and mental toughness, with the “mental” side usually relying on “willpower” and “character”– without training equivalent to physical training. People can’t “think their way” to physical fitness (as my waistline indicates!) and they can’t “will their way” to emotional resilience. They need to be taught how to deal with emotional traumas, have practice in those techniques. There are new programs aimed at pre-trauma instruction and post-trauma treatment, with specific directions to commanders not to ignore soldiers’ mental/emotional state, but it’s a slow transition. A lot of inertia.

Coming back to your original question: it’s unrealistic to write about military conflicts without acknowledging both physical and mental/emotional trauma…otherwise you’re writing video-game conflicts, in which little electronic figures go poof and your score rises and there’s no smell, no mess, no nightmares. So injuries — from minor to life-altering to fatal on the physical side, and the equivalent on the mental/emotional side — are naturally part of any story that involves war, and should, in my view, be part of any story set in war. And the same with families: soldiers aren’t hatched from vats. They have backstory: they were children, with parents or guardians, siblings or no siblings, schoolmates, a cultural milieu, all of it shaping their attitude towards the military they joined (or were drafted into.)

Byrt: You’re currently working on a continuation of the Paksenarrion series – can you tease a little bit about what’s coming up in Kings of the North? (And will there be anyone from Paks’ unit who gets a quiet, happy retirement? I ‘m starting to feel bad for all of them… :)

EM: What’s coming up? Love, war, treachery, revelations, skullduggery, assassinations, escapes, and a scene in which every woman will imagine her favorite male actor and men will be glad they were never in that situation. Readers of Oath of Fealty have met two of the kings, Mikeli of Tsaia and Kieri of Lyonya. The new book introduces another and very different king. And his difficult daughter.

EM: What’s coming up? Love, war, treachery, revelations, skullduggery, assassinations, escapes, and a scene in which every woman will imagine her favorite male actor and men will be glad they were never in that situation. Readers of Oath of Fealty have met two of the kings, Mikeli of Tsaia and Kieri of Lyonya. The new book introduces another and very different king. And his difficult daughter.

Someone in the former Duke’s Company will get a quiet happy retirement (for awhile at least) in the book I’m working on now. I can’t promise it will stay that way. Some characters seem to put on that red shirt with determination.

Byrt: What else is on the horizon for you? Do you have any plans to return to your Vatta series, or start another military space series down the line? (Fingers crossed…)

EM: No firm plans beyond getting this group of books finished. I’ll find out what’s next when I’m closer to it.

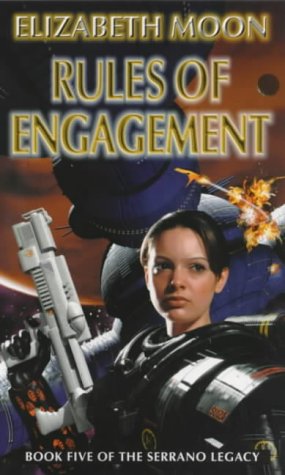

Byrt: You’ve been on the receiving end of a lot of political vitriol in recent weeks, and it actually made me think of Esmay’s situation in Rules of Engagement. Is this something you’ve seen or experienced before? Or is this a new breed of hostility, born of our current media/political environment?

EM: I’ve seen it before, yes, and have been the target of it by both sides in previous rows (it was possible to be called a warmonger and a pacifist in the same 24 hour period, spat on by one side and sneered at by the other.) It’s not really a new kind of hostility — you can find it all the way back in history. In the 20th century, Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, and others roused mob emotions and violence and used what were then modern means of communication to gain their ends. What’s new is the technology that makes rousing and gathering a much larger like-minded crowd much easier. The methods have become the default for political communication, for both Left and Right (and every other division.)

EM: I’ve seen it before, yes, and have been the target of it by both sides in previous rows (it was possible to be called a warmonger and a pacifist in the same 24 hour period, spat on by one side and sneered at by the other.) It’s not really a new kind of hostility — you can find it all the way back in history. In the 20th century, Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, and others roused mob emotions and violence and used what were then modern means of communication to gain their ends. What’s new is the technology that makes rousing and gathering a much larger like-minded crowd much easier. The methods have become the default for political communication, for both Left and Right (and every other division.)

Byrt: And lastly, have you read any good books recently that you’d recommend?

EM: More than I can list, so I can name only a few and hope those writers I don’t mention will forgive me and understand the limitations. In this genre, Kate Elliot’s Cold Magic, Laura Bynum’s Veracity, Nnedi Okorafor’s Who Fears Death, Terry Pratchett’s I Shall Wear Midnight, and most recently (just extracted from my husband’s clutches) Lois McMaster Bujold’sCryoburn.

Non-genre fiction is probably the smallest category this past year (I tend to re-read old favorites) but I very much enjoyed Mueenuddin’s collection of short related pieces, In Other Rooms, Other Wonders.

Nonfiction makes up at least half of my reading, both direct research for the current work, and general “keeping up with other interests.” Margaret MacMillan’s Dangerous Games: The uses and misuses of history points out the ways that every culture shapes its own mythology and falsifies its past — and the consequences of doing so. (Nobody gets a hall pass…) Thomas De Waal’s The Caucasus: An Introduction is an amazingly coherent account of that very chaotic region. I bought MacMillan’s book last year, but have read it through the year alongside other history-based nonfiction, including both newer purchases like De Waal’s book, and rereading older ones. I realize looking at the list that although I feel like I have no time to read I have actually read quite a few. The to-be-read stack, though, has not shrunk. Nor has the wish list. (SFnal wishes: a higher-speed input system for the information in the nonfiction books and a much better storage/indexing system for the information once it’s in the brain.)

Nonfiction makes up at least half of my reading, both direct research for the current work, and general “keeping up with other interests.” Margaret MacMillan’s Dangerous Games: The uses and misuses of history points out the ways that every culture shapes its own mythology and falsifies its past — and the consequences of doing so. (Nobody gets a hall pass…) Thomas De Waal’s The Caucasus: An Introduction is an amazingly coherent account of that very chaotic region. I bought MacMillan’s book last year, but have read it through the year alongside other history-based nonfiction, including both newer purchases like De Waal’s book, and rereading older ones. I realize looking at the list that although I feel like I have no time to read I have actually read quite a few. The to-be-read stack, though, has not shrunk. Nor has the wish list. (SFnal wishes: a higher-speed input system for the information in the nonfiction books and a much better storage/indexing system for the information once it’s in the brain.)

Thanks again to Elizabeth for taking the time!

And for more on all things Moon, you can find her websites here and here.

I was also saddened by the vitriol spewed at Elizabeth Moon over a few sentences taken out of context. I would hope that in the political sound byte culture that readers would still be interested in the whole story, reasoned argument, and nuance. Flame emails are for the 12-and-under set. Tweens have an excuse — they haven’t developed complete frontal lobes yet. Anyone else accusing the author of Speed of Dark of shallow thinking should consider calming their passionate political reflexes and put their reading and thinking hats on. After all, if it’s more interesting to explore and understand different characters’ points of view in fiction, why not extend the same interest to people in real life?