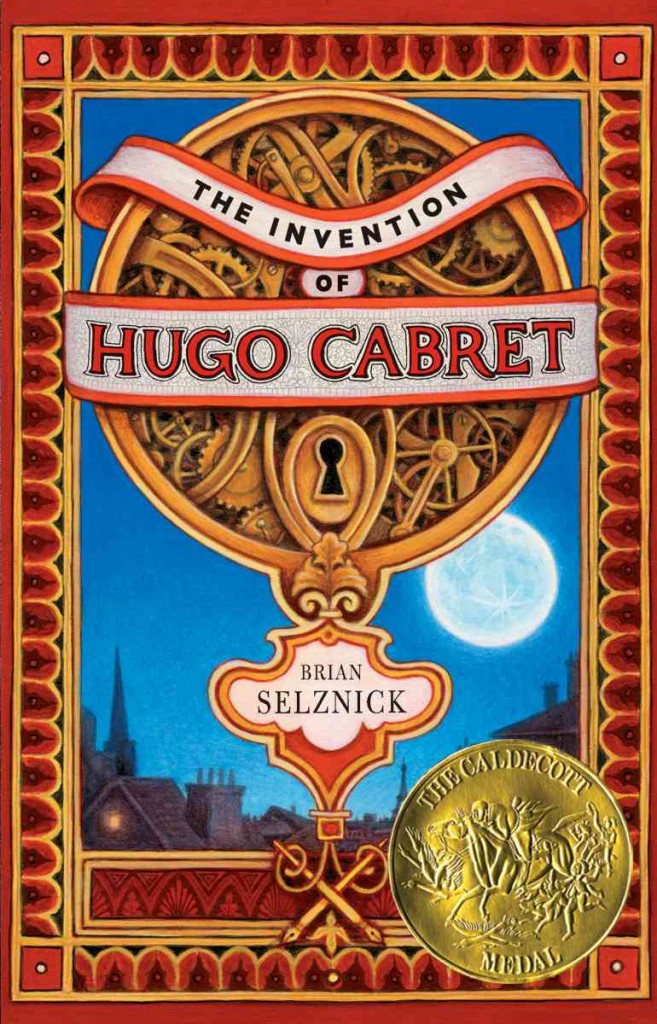

Book Jacket:

Orphan, Clock Keeper, and Thief, twelve-year-old Hugo lives in the walls of a busy Paris train station, where his survival depends on secrets and anonymity. But when his world suddenly interlocks with an eccentric girl and the owner of a small toy booth in the train station, Hugo’s undercover life, and his most precious secret, are put in jeopardy. A cryptic drawing, a treasured notebook, a stolen key, a mechanical man, and a hidden message all come together…in The Invention of Hugo Cabret.

This 526-page book is told in both words and pictures.The Invention of Hugo Cabret is not exactly a novel, and it’s not quite a picture book, and it’s not really a graphic novel, or a flip book, or a movie, but a combination of all these things. Each picture (there are nearly three hundred pages of pictures!) takes up an entire double page spread, and the story moves forward because you turn the pages to see the next moment unfold in front of you.

You can watch the opening sequence of drawings here.

Review:

This is a story that teeters on the verge of being great, but in the end I have to call it merely good.

There is a lovely core to this book, about the magic of dreams and how one man’s dreams, preserved on film, help a boy discover his own. The book was inspired by – and is in large part a tribute to – George Méliès, a director perhaps known only to film history buffs. Méliès was a magician turned filmmaker who famously created the first science fiction/fantasy film, A Trip to the Moon, back in 1902 .

In 1913 Georges Méliès’ film company was forced into bankruptcy and of the 500 films he made, most were lost or destroyed. Méliès faded into obscurity. I would bet good money that paying homage to Méliès is a large part of why Martin Scorsese is directing the feature adaptation of this book. (Scorsese is dedicated to the preservation of film history, and he founded a non profit – The Film Foundation – to do just that.) I absolutely love that through this story kids will learn Méliès’ name.

In Hugo Cabret, Méliès’ famous film plays a central role in the mystery surrounding an automaton that one orphan boy, Hugo Cabret, is determined to fix. Hugo is obsessed by the machine, convinced that if he can just make it work again it will somehow magically rescue him. His quest to fix the automaton brings him to the owner of a toy booth, who has secrets of his own, and his nosy granddaughter. Together they threaten to make Hugo’s carefully hidden world fall apart.

There are plenty of chase scenes in this book, where Hugo is almost caught by the authorities, and while they become a little repatative, they add a nice drive to the narrative. The gears of clockwork, the automaton, and the mystery surrounding the toy seller are all fascinating – my problem with this story is that while there is a wonderful build up, there is no finale. The story fizzles and sputters to an end because the emotional arc flatlines – the toy seller is on the verge of a breakdown because of some dark secret he is desperate to keep hidden, but as soon as Hugo and the man’s granddaughter uncover it, he’s just fine. Too fine. The toy seller goes from crazed and feverish to suddenly coherent and content in the blink of an eye, with no real explanation or understanding of his transformation. I can extrapolate some, and guess at more, but mostly I just feel cheated. I badly wanted him to have his moment, to see his revelation, to understand what went through his mind.

Hugo’s ending is similarly anticlimactic – the orphan finds a place to belong much too easily. A large part of what’s missing from the end of this book is Hugo’s role in the toy seller’s metamorphosis and vice versa. They both shake up each other’s world, and we go from things crumbling around them to everything being shiny and happy. We’re missing a hugely potent emotional step – it’s like someone fell overboard and then we cut to them safe, back on the dock. For this story to fully deliver, we would have to see and feel that moment when they rescue each other. So while there is nothing about the ending to make me actively dislike it, it also didn’t fully deliver. There’s something painful in watching a story fall so far short of its potential.

This book’s unusual format – part words, part graphic novel – I found a little annoying only because it was jarring to go back and forth. Frankly I would have preferred the traditional use of illustrations, but I can’t complain too much because the drawings themselves are utterly fantastic. I feel like illustrations are something of a dying art these days and I hope this book (and Scott Westerfeld’s Leviathan series) convince more people to incorporate them, because they add something special.

At heart this is a lovely story about the magic of film and how one boy finds his place in the world due to the legacy of a filmmaker all but forgotten today. There is magic in this story – a vintage, uncynical, childlike sense of magic and wonder, like what you find in The Polar Express. There is also an old school sense of awe at movie magic – and it is entirely fitting that such a book was written by Brian Selznik, a man descended from the famous Hollywood producer David O. Selznik.

There is something special about this book – a lovely world with fascinating puzzles, both physical and mental, and a touching story. It’s only in its lack of ending that it falls short of being truly great. Still, there is plenty of wistful joy to be found in reading this story – it will remind you of when you used to believe in magic.

Byrt Grade: B+/A-

As Levar Burton used to say – you don’t have to take my word for it…

Methodically, Selznick drives this story past its origins as a simple cat-and-mouse chase, turning it into a mini-history of cinema’s silent era, as well as a meditation on the contraptions that captivate us. The Invention Of Hugo Cabret is meant to be one of those contraptions, and while Selznick’s drawings lack the sense of animation and narrative drive that traditional cartooning requires—and while his prose is functional at best, fussy at worst—the book’s formal daring is delightful in and of itself. And it’s not just about Selznick showing off either. He’s evoking myths, and ruminating on the potential of both objects and people to be more than they seem.

The story combines elements of mechanics, magic tricks, and early film history, and the illustrations evoke a sense of wonder and intrigue. While I liked the book overall, I don’t think the story would be as special without the illustrations. In fact, other than a few intriguing elements (like the automation), the text portions of the story were a little slow and repetitive–I felt the story had a bit of a shallow feel to it.

Young Adult Books Central says:

This book is an amazing, unusual experience. The text of the story is amplified and carried via pages and pages of charcoal drawings, old photos, and movie stills. Interlocking mysteries pull the reader in; these are resolved in a satisfying yet not overly tidy manner, with an ending that made me smile (and brought a tear to my eye). Very highly recommended.

Leave a Reply