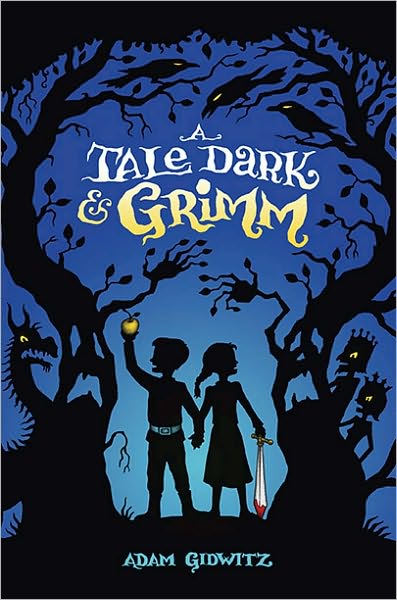

Book Jacket:

In this mischievous and utterly original debut, Hansel and Gretel walk out of their own story and into eight other classic Grimm-inspired tales. As readers follow the siblings through a forest brimming with menacing foes, they learn the true story behind (and beyond) the bread crumbs, edible houses, and outwitted witches.

Fairy tales have never been more irreverent or subversive as Hansel and Gretel learn to take charge of their destinies and become the clever architects of their own happily ever after.

Review:

A Tale Dark and Grimm is a surprise and a delight in how it honors the original Grimm stories, more so than any other Grimm-based book I’ve read – this is a story that is utterly, entirely, and brilliantly true to the spirit of the Grimm fairy tales. Yes, even the dark and disturbing parts, and therein lies the genius of this book – by restoring the sinister nature of classic fairy tales, Gidwitz has gleefully subverted the sanitized, politically correct ideals of children’s literature and served up exactly what kids want to read, all the while reminding us all that children are whom these fairy tales were always intended for.

But before you start thinking this book is some kind of macabre horror story, it’s not. It’s just fairy tales, as they once were – sure, there’s blood and occasionally a severed body part, but always in a safe, fairy tale kind of way. Gidwitz also provides a cheeky narrator that peppers the story with humorously dire warnings. in meta fashion, about what’s coming up next:

Now that’s not a bad little story. But it is a crime, a crime, that that is the only part of Hansel and Gretel’s story that anyone knows.

Yeah, yeah, nearly getting eaten by a cannibalistic baker woman is bad. But it’s not nearly as bad as what’s to come.

Speaking of which, the little kids might have liked that one. Or at least, they probably could have sat through it without screaming their heads off.

In fact, if any little kids heard that story, that’s just fine. Hi, little kids. But things get much worse from here on. So why don’t you go hire a babysitter, and let’s do the rest of this thing alone.

Though the narrator’s preponderance of warnings does quickly get grating, it’s offset by fun snarking at the inevitably ridiculous parts of any fairy tale:

No, of course it can’t. The moon can eat children, and fingers can open doors, and people’s heads can be put back on. But rain? Talk? Don’ be ridiculous.

Good thinking, Gretel dear. Good thinking.

And you can’t help but admire the deliberate nature of the narrator’s commentary – the bevy of dire warnings at the beginning, it’s more than just teasing; it’s also a quiet dare for readers to find the courage to keep going. As Hansel and Gretel face test after test of their courage, the reader is essentially doing the same, by reading along with them. So as the reader is watching Hansel and Gretel grow wiser (while always maintaining their childlike innocence), the narrator seems to be marking the readers’ growth, with the narrator’s rising respect for the reader changing the tenor of the commentary; and as the book progresses the narration gradually becomes less condescending and more the type of wisecracks shared between friends and equals. It’s a lovely device, both for delivering humor and for involving the reader in the story, and it is very cleverly done.

In terms of the story, Gidwitz takes Hansel and Gretel and spins them out across several of the less famous Grimm tales – Faithful Johannes, The Three Golden Hairs, and Brother and Sister. to name a few – tying them all together into a larger story. I’ll admit at first it seemed like a fairly thin device for stringing together a bunch of Grimm fairy tales, and the transitions between the various tales felt forced, but as the story continued and as the retellings gradually opened up, and became a tad less faithful to the Grimm stories, this book managed to meld itself together into a coherent and satisfying larger story. Gidwitz weaves his own narrative into the story so gradually, slipping his originality through the cracks and crevices, that you honestly won’t notice when his voice takes over – you literally can’t tell what is and isn’t Grimm.

A cannibalistic baker, sarcastic ravens, a marauding dragon, murders, and mutalations – this book has it all; but at it’s heart, this is a story about the many ways in which adults can fail children. I do think this book is completely appropriate for children, but I am spectacularly biased, seeing as I grew up on Grimm fairy tales myself, without suffering any ill effects (that I’m aware of…). But if you’re a parent who can’t help but panic at the idea of your child reading about a cannibalistic baker, here’s what Gidwitz has to say in response to concerns about the violence in his book:

Fairy tale violence was made for kids—especially, in the case of the original Grimm, kids five and over. Or in the case of my book, kids ten and over. Unlike most of the movies that parents take their kids to see these days (Transformers, pretty much any action flick) fairy tales are told with children in mind. That means that fairy tales, despite the blood, are truly appropriate for children. They are, crucially, emotionally appropriate for children.

In any case, A Tale Dark and Grimm is just good creepy fun. It might start out a bit stilted, but it comes together nicely in the end. Given the recent spate of fairy tale re-tellings, it is a rare and wonderful thing to see a story that honors the source material in such a loving way.

Gidwitz puts the grim back in Grimm, in the best possible way.

Byrt Grade: A-

As Levar Burton used to say – you don’t have to take my word for it…

Marjorie Ingall for The New York Times says:

…A Tale Dark & Grimm is really, really funny. The first line is “Once upon a time, fairy tales were awesome.” The tone ricochets between lyrical and goofy. There’s an intrusive, Snicket-y narrator who warns the reader every time gore is imminent, apologizing, urging the reader to hustle the little kids out of the room. And it all works. As the story progresses, it gets less and less faithful to the source material and becomes its own increasingly rich and strange thing. A Child’s Garden of Metafiction! It reminds me of Eudora Welty’s Robber Bridegroom, in which bits of fairy tales, myths, legends and Southern folklore are stitched together into a marvelous new . . . something.

I decided to inspect the stories Gidwitz appropriated to see exactly how closely they adhered to the originals. I was not disappointed. “Faithful Johannes”? Dead on, including the whole kidnapping the mom bit. “The Devil With the Three Golden Hairs”? At points, nearly word for word. He’s often faithful, but sometimes I wondered if Gidwitz was calling upon versions of tales even older than the Grimm’s. The fact that the witch in the story “Hansel and Gretel” isn’t a witch at all but a baker feels like an earlier version of the story. I began to wish that Gidwitz would mention what his sources were when writing this tale. Because even if the baker idea was his own, it feels incredibly authentic…I was most intrigued when Gidwitz was at his most original. The story “Brother and Sister” seemingly has little to do with the original tale except that a boy and a girl are living on their own in a forest and the brother is turned into a wild beast. The story “A Smile As Red As Blood” seems closest to “The Robber Bridegroom”, complete with the telltale finger. It might be mixed with another story as well, though. The detail about killing warlocks by boiling them in oil with poisonous snakes felt a little too authentic. After reading for a while, you begin to find you cannot separate Gidwitz’s writing from that of the Grimms. At the beginning of the book they are distinct and separate. The Grimms are almost word for word and Gidwitz just throws in a little snarky commentary. Then as the book progresses, more and more of Gidwitz seeps in so that by the end it’s impossible to say what is and isn’t authentic Grimm.

Fairy tales for the horror set blend themselves into one intact thread that’s satisfying enough to overcome an intrusive narrator.

Leave a Reply